Private Henry Alfred Emerson

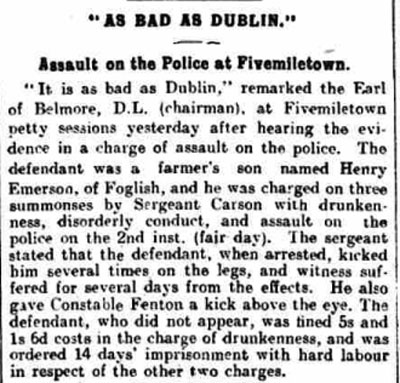

Henry Alfred Emerson was born on 8 July 1886 at Foglish, Brookeboro, County Fermanagh, the fifth of six children of farmer Edward Emerson and his wife Margaret Jane (née Maguire). At the time of the 1911 Census he was living at Foglish with his parents and two of his four surviving siblings, and working on the family farm. At the beginning of 1914 he fell foul of the law for an incident at Fivemiletown on 2 January (see article below).

Belfast News-Letter, 15 January 1914

Emerson enlisted in the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons Service Squadron on 10 October 1914 (No.UD/23). He embarked for France with his squadron on 6 October 1915. At the time they were serving as divisional cavalry to the 36th (Ulster) Division.

In June 1916 Emerson's squadron came together with C and F Squadrons of the North Irish Horse to form the 2nd North Irish Horse Regiment, serving as corps cavalry to X Corps. In September 1917 the regiment was dismounted and most of the men were transferred to the infantry. After training at the 36th (Ulster) Division Infantry Base Depot at Harfleur, the men, including Emerson, were formally transferred to the Royal Irish Fusiliers on 20 September and soon after were posted to the 9th (Service) Battalion – re-named the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion – joining it in the field at Ruyaulcourt. Emerson was issued regimental number 41103 and posted to A Company.

He probably saw action with the battalion at the Battle of Cambrai in November and December 1917.

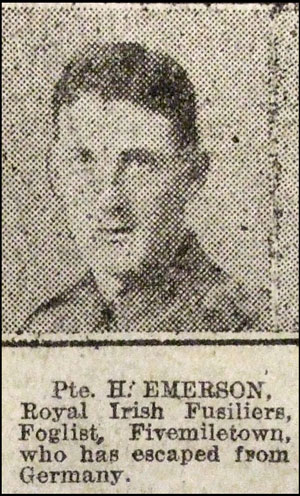

Emerson was one of the many listed as missing following the 9th (NIH) Battalion's fighting withdrawal from St Quentin from 21 to 28 March 1918 during the German spring offensive. It was later learned that he had been captured, most probably east of Erches on the 27th. Held at a number of prisoner of war camps in France, on 15 September he and another man escaped from Fresnoy-le-Grand and made their way to the nearby allied lines. Emerson's account of his period in captivity is given below:

I was captured unwounded and did not during my time as a prisoner go into a hospital. I was captured with the 108th Brigade, and only three officers were left to be taken, Mr. Scott, Mr. Smith and Mr. Breminer, all lieutenants. They were the only officers left in my company, A company. We were cut off for two days before we were captured, and for three days after our capture we received no food.

Nesle. March 28-29, 1918. We were kept in Nesle for one day.

Ham. March 29-30, 1918. We were kept one day at Ham. I was never searched or interrogated at all. We stayed in cages during the nights before we got to St. Quentin in old buildings. During the three days we were simply marched about. There was no ill-treatment during that three days. There were some wounded, and men were told off to look after them. The wounded got very little medical attention, and there were plenty of bad cases among them. We were given water to drink, and we were not interfered with.

St. Quentin. March 30 - April 21, 1918. I was taken to St. Quentin on the 30th March. I remained for three weeks. At St. Quentin we were put in what had been a cottage or cow-house. There were French prisoners there as well. There were no beds or blankets given us, and our clothes were never off us. It was very cold weather, and there was no heating apparatus, not even a roof on the buildings. The food here was a small loaf of black bread to four men per day (1,400 grammes of bread to each four men); soup, very thin, once a day, preserved turnips seemed to be in it; coffee made of burnt barley; tea in the evenings, only it was not tea; no meat, no fats. There was only a small quantity of each kind of food, and all them men got very low on this diet. No clothes were taken away from us, I was captured with just the clothes I stood up in. The work I had to do here was burying the dead. I spent the whole of the three weeks at this. The guard indulged in plenty of abuse and knocked us about, but I do not know any case of any man being badly injured. The place we were accommodated in was called Martin-Henri. We were in big rooms with the roofs all shattered, and not wired round. The latrines were old places dug out in the yard. It was very filthy and dirty, and there was no payment for work. It was not until my last week at St. Quentin that I was allowed to write home. I was then given a field card and I addressed it to my home. I don't know when it reached there. I received no clothing from the Germans. I did not ask for any, but I do not think I should have received any if I had done so. The German soldiers were short themselves and offered to buy clothes from us. I never received any letters from home there or anywhere else while a prisoner. I never received any parcels, and nobody with me did. The German guards at St. Quentin had better rations than we did. No persons died at St. Quentin while I was there. There were only Portuguese and French and a few Russians there; I think the French had the best treatment. Our men cooked for the whole of the prisoners; they would also get better jobs.

Esmery-Hallon. April 21 - June 30, 1918. From St. Quentin I was taken with 40 others, all British, to Esmery-Hallon, 6 kilom. south of Ham. This was about the 21st April, and I remained there until about the 30th June. At Esmery-Hallon we lived in an old building, no roofs, no beds, no blankets, no protection from the weather. I remained all the time I was there in this building. I had just the clothes I stood up in and nothing else. The food here was just the same as at St. Quentin. We worked here as engineers, cutting timber, digging holes, and erecting an electric cable. We worked eight hours a day; no night work, no payment received. Worked the eight hours straight through without a spell. The latrines here were very bad, filthy and dirty, and a very bad stench. There was plenty of ill-treatment from the guards, abuse and beating with rifles, and kicking. This the guard did to anyone, not only when there was a refusal to work. I do not know of anyone who had bones broken. The guards, both at St. Quentin and here, were old men who had never been in the line. Only once was I allowed to write home from here. This was about the middle of May, and I do not know whether this got home. The other men there, at this time, were only allowed to write home this once. No mails or parcels were received, and we received no clothes here. We worked seven days a week here also. There were very few smokes. A German corporal was in charge of the camp; there was a camp commandant, but he never came near it. There were two British sergeants there, and they were made to work also. There was a hospital there for those who went sick, but they had to be very bad before they were sent there. There was no doctor at the camp, and if a man reported sick, he went to the hospital and it was decided there. I think the treatment in the hospital was not so bad. The guards at Esmery-Hallon had better rations than we had. There was no canteen here, and there was no time allowed us for recreation. There was plenty of sickness, dysentery, and some disease like dropsy. When at Esmery-Hallon we used to be taken down the line to work at a place called Ognolles, near Roye, and were shelled there. There were no casualties, but shells used to fall all round us. We worked most of our time there, and we had to walk here, a distance of about eight kilom. That means we had to walk 10 miles a day, besides doing our day's work. No prisoners died at Esmery-Hallon while I was there.

Fresnoy-le-Grand. June 30 - July 6, 1918. About the 30th June I was moved to Fresnoy-le-Grand with my party. I remained here six days, while waiting to go to Hautmont. We did no work here, and were given only half rations. We lived in a cow-shed without any conveniences, no bed, or blanket, or covering.

Hautmont. July 6 - Sept. 9, 1918. I was then taken to Hautmont, near Maubeuge, where I remained until the 9th September. At Hautmont we were accommodated in an old building which had a roof. We had no beds or blankets. We worked at a salvage dump, eight hours a day, seven days a week, pretty heavy work. We received pay here, 1s. 2d. per hour. The food here was just the same as at Esmery-Hallon, but the treatment here was bad. We were beaten and kicked by the guard. This was the usual thing; The guards constantly ill-treated us like this. There was no one to complain to; if we complained to an officer, he would give us the same. I wrote home from here, but I do not know whether it reached home. In this letter we were told to give an address for our letters to be addressed to. This address was: The Roumanian Command, No. 7, Stendal, Germany. Some men got letters here, but not with this address. No parcels were received in my time. There was no canteen and no means of buying anything. I saw Italian prisoners at Hautmont; they were getting good treatment.

Fresnoy. Sept. 9-15, 1918. On the 9th September I was taken back to Fresnoy, and escaped from there on the 15th September. At Fresnoy there were 1,500 Portuguese prisoners when I escaped. All these men had been captured since March, and were to go to Germany on the 16th. The brigade had been split up, and some had been kept to work behind the lines, and some had been sent to Germany. My treatment behind the lines was just the same all the time; no improvement. ...

Opinion of Examiner. This was a difficult witness; willing, seemingly, but one who found it difficult to express himself. He gave me an impression of having received worse treatment than he was able to express clearly.

(From Prisoner of War interviews, No.2536, National Archives, Catalogue Reference WO/161/100/445.)

On 11 March 1919 Emerson was demobilised and transferred to Class Z, Army Reserve.

Images of Emerson, from the Belfast Evening Telegraph, kindly provided by Nigel Henderson, Researcher at History Hub Ulster.

This page last updated 16 January 2023.